Cities everywhere are doing a lot for entrepreneurs, often sincerely and impressively, and what I’m finding in city after city is that the greatest opportunity is not in another startup program or even fostering a new investor but building capacity. They are supporting some founders, but not more founders. They are helping some investors, but not bringing new capital into the market. They are delivering programs, but not producing system-wide throughput.

Talk to economic-development teams in New Mexico, Alberta, Queensland, Lisbon, or Tulsa and the pattern sounds uncannily familiar. They’ve launched accelerators, pitch competitions, public–private task forces, grant programs, and “innovation districts.” Yet their deal-flow density stays relatively flat, their mentor pools age out, and their best startups outgrow the region long before the region grows into what they need.

The problem is not that cities aren’t doing enough. The problem is that cities aren’t expanding their capacity to serve more of the entrepreneurs, mentors, and investors that a competitive economy now requires. As Brookings has pointed out in their analysis of innovation clusters, ecosystem performance is a function of network depth, institutional coordination, and resource density. Resource density is the giveaway. Most cities don’t lack activity; they lack density, coordination, and the infrastructure that makes tens of thousands of entrepreneurial decisions possible each year.

The OECD, likewise, concluded that capacity building must focus on enhancing entrepreneurial support systems, strengthening intermediary organizations, and improving human capital pipelines, particularly in regions seeking to diversify their economies.

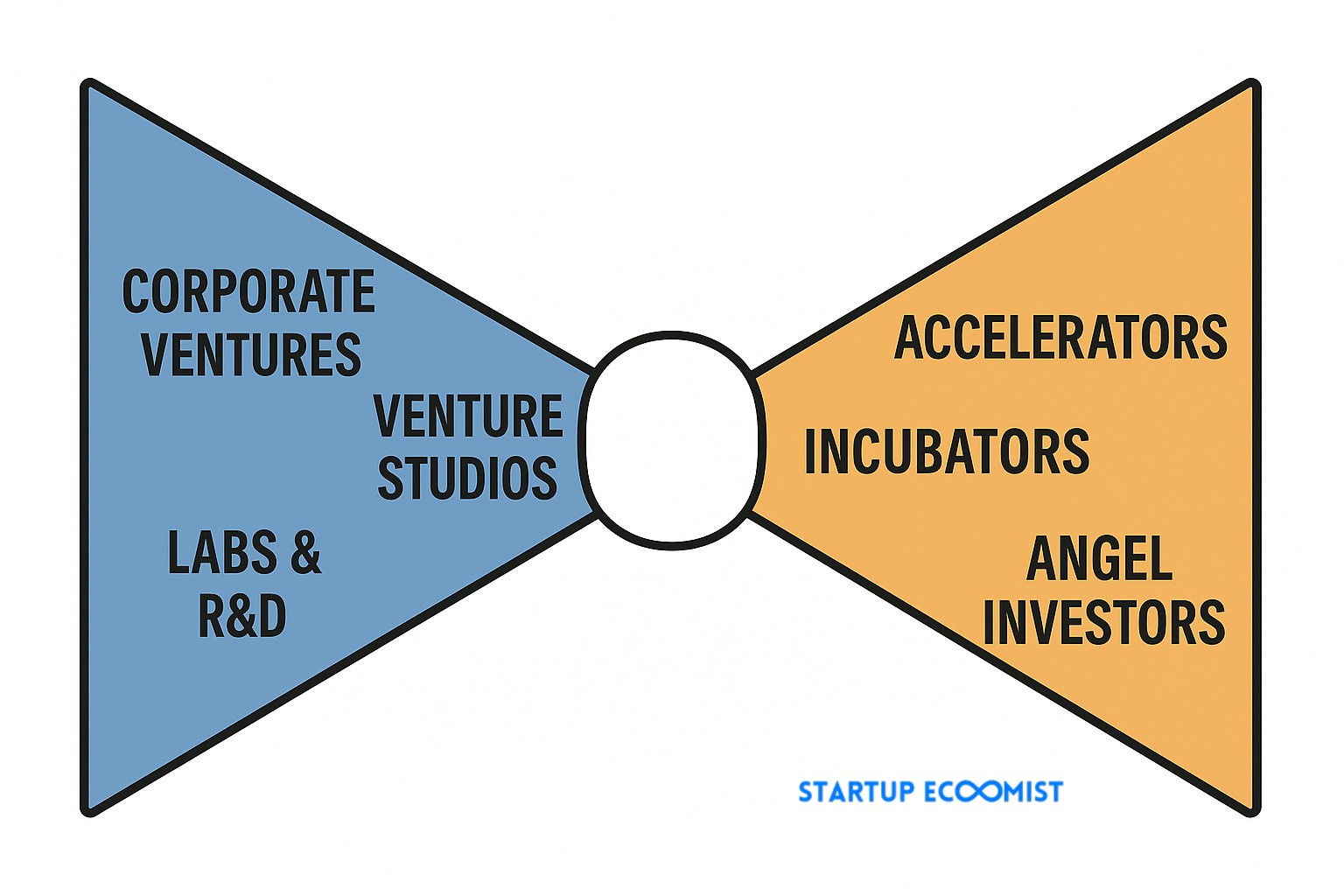

And that’s the paradox. Cities are building things that look like startup ecosystems, while the underlying throughput resembles a two-lane frontage road at rush hour. Most communities still collapse at the knot of the bow tie; the point where early-stage aspiration is supposed to transition into real growth. Most cities simply don’t have the lanes, the exits, the signage, or the on-ramps necessary to move hundreds of founders through to market traction, capital formation, and scale.

Capacity building is the hard, unglamorous engineering work of widening the freeway.

Let’s talk about the ten dimensions of entrepreneurial capacity that economic-development leaders must confront.

1. Overcoming Silos: shared infrastructure, shared memory, shared momentum

Ecosystems stall because information moves slowly, repetitively, or not at all. Universities run their programs. Chambers run theirs. Accelerators build cohorts in a bubble. Government agencies maintain parallel databases. Everyone “supports entrepreneurship,” yet founders navigate a maze where every door leads to a different map.

Silos destroy throughput.

MIT’s Regional Entrepreneurship Acceleration Program found that ecosystems with strong collective governance and shared infrastructure outperform those where actors remain isolated. Shared infrastructure means, for example, a common CRM for founders (why not?), collective storytelling, unified mentorship standards, and consistent deal-flow pipelines.

What to do: create a single interface for entrepreneurs; treat every organization as a node in one network rather than one more isolated program. Better? Obligate that startup development organizations in your ecosystem are promoting one another, freely sharing all mentors and investors, and referring founders to the resources more ideal than perhaps their own (or shut them down because they’re contributing to the silos that limit entrepreneurs)

2. The Missing Middle: the widening gap between nascent startups and established companies

Economic development traditionally focuses on small business support and corporate attraction. But between those poles sits the high-growth, pre-scale firms that need mentorship, capital, and technical support long before they qualify for incentives or bank financing.

High-growth new firms are responsible for a disproportionate share of net new jobs. Yet these companies often die in the gap between ideation programs and investor readiness. That gap is exacerbated by what are likely other middle gaps also a challenge in your ecosystem such as capable marketers, mid-career jobs, and Series A funding, just to name a few of the commonly cited gap issues in cities throughout the world, “we have stuff on this side and for that side but nothing can cross the chasm.”

What to do: build mid-stage supports such as B2B customer access, fractional executives, applied R&D partnerships, and capital-readiness preparation.

3. Funding the Actors: not venture capital for startups, but stable, multi-year support for ecosystem builders

Every ecosystem quietly relies on a handful of people: connectors, mentors, operator-founders, nonprofit teams, program managers, analysts, community architects, marketers, and scouts. Most are underfunded. Many burn out. Some quit in exhaustion because no one supports them.

The National League of Cities concluded that sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems depend on sustained investment in intermediary organizations and local leaders.

Cities pour millions into corporate recruitment incentives while asking ecosystem builders to charge $25 tickets to a startup event just to keep the lights on because the local law firm won’t sponsor any more than a few thousand dollars.

What to do: provide multi-year operational funding, not short-cycle grants; treat ecosystem builders as infrastructure, not event planners.

4. Measuring Outcomes, Not Activity

Events are not outcomes. Demo days, pitch competitions, and hackathon participation are signals of interest, not economic performance.

Capacity building requires metrics tied to throughput, such as:

- funding per capita

- new angel investors activated per year

- number of scalable startups reaching $1M+, $5M+, and $10M+ revenue

- local corporate procurement awarded to local startups

- exits and liquidity events

Ecosystems obsessed with activity create vanity metrics that move no capital, change no culture, and mislead policymakers. What matters is whether you can repeat success.

What to do: adopt metrics tied to growth, traction, and capital formation, then promote those stories relentlessly to create gravitational pull.

5. A Culture Where Collaboration Is Normal, Not Negotiated

Collaboration often dies in the same place innovation does: at the boundary between organizations competing for relevance, credit, or funding.

Stanford’s research on ecosystem performance shows that trust and informal collaboration networks are strong predictors of early-stage innovation output. Yet many cities treat collaboration as a memo instead of a habit.

What to do: build rituals that force cross-pollination such as shared mentor pools, cross-organization cohorts, integrated communications channels, and standing ecosystem roundtables. I’m revisiting consideration #1 a bit to reiterate that it’s on you to require this of startup development organizations (and don’t take their word for it that they are, ask the people you’re supporting in #3 because they’ll tell you about the bad actors)

6. Include the Invisible Talent not just the visible founders

Most ecosystems empower the people already on stage: serial founders, credentialed executives, alumni of recognizable companies. But the OECD warns that untapped entrepreneurial potential disproportionately exists among people outside established networks.

I see this all the time where over a decade, the same handful of people repeatedly win your annual awards, are featured in local press, and give the speeches and panel talks. You’re not recognizing the leaders, you’re ignoring the majority that matter.

What to do: broaden discovery. Never limit the stage to members or paying partners. Build outreach teams. Use founder-assessment tools rather than resume filters. Ensure “openness to outsiders” (the trait the best ecosystems have in common).

7. Architect Environments Where People Perform at Their Highest Potential

Entrepreneurship is not merely a function of talent; it is a function of conditions. Workspace design, mentorship availability, early customers, access to prototyping resources, and even psychological safety determine whether a founder moves fast or stalls.

Environmental context determines the likelihood that entrepreneurial intention becomes entrepreneurial action.

What to do: build spaces, norms, and tools that remove friction from every step, from IP support to B2B sales to freely available physical space to mental-health support for founders.

8. Align Government, Academia, and the Private Sector, the hardest knot in the bow tie

Government moves slowly, academia moves cautiously, and the private sector moves according to incentives. Alignment requires shared outcomes, shared data, and shared language.

Government moves slowly, academia moves cautiously, and the private sector moves according to incentives. Alignment requires shared outcomes, shared data, and shared language.

This is precisely where most ecosystems break, as I explored in a bow-tie analogy. Cities invest in “on-ramps” (programs, workshops, accelerators) but fail to tighten the knot where founders transition into revenue, customers, and capital. Universities produce research without commercialization pathways. Governments offer incentives but not deal flow. Investors wait until traction exists, long after the region has lost half its would-be founders.

What to do: implement a single strategic operating framework such as what we have in Founder Institute for cities, define shared KPIs across all partners, and appoint ecosystem stewards with authority to coordinate across institutions.

9. Accelerate Innovation by Unlocking Local Competitiveness

Regions rarely understand their own comparative advantage. They chase whatever trend is hot so as to appear innovative (crypto conferences, AI hubs, Web3 zones, biotech corridors) rather than building around the strengths their talent, industries, and institutions already offer.

Pace-based innovation succeeds when it aligns with regional industrial capabilities and existing knowledge domains.

If you’re saying “tech sector,” you’re doing it wrong because tech isn’t a distinction.

What to do: map local industry clusters, commit to two or three defensible strengths, and build founder services tailored to them. Focused ecosystems outperform generic ones.

10. Adapt Global Best Practices (don’t copy them!)

Cities love to import templates: “Let’s be the next Austin.” “Let’s go with that partner because they’re dominant in Silicon Valley.” “We need an accelerator like Boulder.”

But ecosystems are not software; they are organisms. Best practices must be adapted to local cultures, industries, risk profiles, and political realities.

Founder Institute, MIT REAP, Startup Genome, and countless global partners consistently emphasize this: the regions that rise are not the ones that copy, but the ones that translate.

What to do: study global models, borrow only the principles, and rebuild the implementation from the ground up for your city’s realities.

The Freeway Analogy to Share with Your Economic Development Team

Most ecosystems have the same problem as most metro freeways.

Insufficient on-ramps.

A couple of exits but rarely in the ideal places.

Lack of transit alternatives while everyone is clearly angry at the congestion.

And signs that confuse newcomers while locals pretend it all makes sense.

Capacity building is freeway engineering: widening lanes, adding ramps, improving exits, synchronizing signals, and making sure the entire network handles volume, not just special-occasion traffic.

Until a city treats its startup ecosystem as infrastructure, not programming, it will always end up with congestion, frustration, and a whole lot of talent taking the first exit out of town.

This work, entrepreneurship and support of it by your city and government, demands more than enthusiasm. It demands capacity: the ability to serve more founders, more investors, and more innovation than your current freeway can handle.

That’s why an upcoming discussion I’ll be hosting with Sameer Sortur, Founding Partner at SquareCircle Ventures, and Faris Alami, CEO of International Strategic Management, is worth your calendar as we’ll focuses precisely on what most cities struggle with: how to create sustainable economic growth by engineering capacity rather than celebrating activity.

You can explore the event and register to join us, here

If your region is running out of lanes, consider this an opportunity to rethink the infrastructure before the next wave of entrepreneurs decides to merge somewhere else.